- Home

- Charlaine Harris

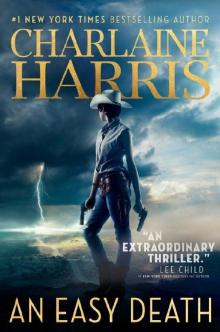

An Easy Death (Gunnie Rose #1)

An Easy Death (Gunnie Rose #1) Read online

Thank you for downloading this Simon & Schuster ebook.

* * *

Get a FREE ebook when you join our mailing list. Plus, get updates on new releases, deals, recommended reads, and more from Simon & Schuster. Click below to sign up and see terms and conditions.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

Already a subscriber? Provide your email again so we can register this ebook and send you more of what you like to read. You will continue to receive exclusive offers in your inbox.

Publisher’s Notice

The publisher has provided this ebook to you without Digital Rights Management (DRM) software applied so that you can enjoy reading it on your personal devices. This ebook is for your personal use only. You may not print or post this ebook, or make this ebook publicly available in any way. You may not copy, reproduce, or upload this ebook except to read it on your personal devices.

Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this ebook you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: simonandschuster.biz/online_piracy_report.

For my husband of so many years, Hal.

I couldn’t have done any of this without you.

CHAPTER ONE

In the morning I got Chrissie to cut off all my hair. Tarken and Martin would be tinkering with the truck, which was our livelihood. Galilee would be watching Martin, because they had started seeing each other before and after work. Or she would be cleaning her little house, or washing her clothes. I never saw Galilee bored or idle.

But I didn’t have to be at Martin’s until late that afternoon, so I was doing whatever I pleased. That morning I was pleased to get rid of my hair.

My neighbor Chrissie was not too bright, but I’d watched her trim her husband’s hair and beard as he sat on a stool outside their cabin. She’d done a good job. She sang as she worked, in her sweet, high voice, and she told me about her youngest one’s adventures with a frog in the creek.

When she was halfway done, she said, “Why you want to cut all this off? It’s so pretty.”

“It gets all sweaty and sticks to my neck,” I said. Which was true. It was only spring now, but it would be the hot season soon.

“You better wear you a hat so your head won’t get all red and tender,” Chrissie said. “You want it so short I think the sun might get your scalp.”

“I’ll take care,” I said, holding up the only little mirror Chrissie had. I could see part of my head at a time. She’d washed it, so my hair was wet. I thought it was about an inch long. Looked like the curl was gone, but I wouldn’t know until it dried.

“You heading out soon? I saw them farmers at Martin’s place, when I was coming back from the store.” Chrissie’s trousers had long tendrils of dark hair all over ’em now. She’d have to brush ’em.

“Yeah, we’re leaving as soon as it’s near dark.”

“Ain’t you scared?”

Sure, I was. “Of course not, the only ones should be scared are anyone who tries to get in our way.” I smiled, my eyes and lips shut against the soap trickles.

“You’ll kill ’em dead, bang, bang,” Chrissie said in singsong voice.

“Yep. Bang, bang,” I agreed.

“Why are they going to New America?”

“The farmers? The part of Texas they live in got swallowed up by Mexico a few years ago. You remember?”

Chrissie looked dim. She shook her head.

“Anyway, the government down there has been telling the Texans that they’re not real Mexicans, and their land is forfeit.”

Chrissie looked even dimmer.

“Their land is getting taken. So if they’ve got kin up north or anywhere, even in Dixie, they got to leave Mexico to have a chance.”

Dixie was so poor and so dangerous you’d have to be desperate to flee there.

Chrissie ran her fingers through the short hair on the left side of my head, and shook her head. “Anyone ever go to the HRE?” she asked.

“Chrissie,” I said. She bent around to meet my eyes.

“Oh, sorry, Lizbeth.” She began to work on the right side, following her own whim. I tried to remember if I’d ever seen her cut anyone’s hair besides Norton’s. “I forgot you don’t like them grigoris.”

No. I did not like magicians.

“Tarken know you’re doing this?” she said after a moment. I could tell by the faraway sound of her voice that the question had come from her mouth, not her head.

“No, he doesn’t have a say in my hair. Don’t you go telling.”

“He’ll see it this afternoon.”

“Yeah, it’s a surprise,” I said.

Chrissie gave me one of those looks that reminded me she was older than I was. “He ain’t gonna like it, Lizbeth.”

I raised up my shoulders, very carefully, because I didn’t want to jolt her hand. “Not his head,” I said, and that was the truth. But it was also true that he’d tried to tell me how I should do something one time too many.

When Chrissie had finished, and the little mirror told me it was cut evenly all over—God knows how—I paid her. She gave me a big smile before she carried the chair inside. She came back out to pump some water to wash her hands, and put some in a bucket to toss around, trying to spread out the long, dark hair that lay in a heap where the chair had stood.

I gave her a hand. When the dirt didn’t look like the sky had snowed black ringlets, I went uphill to my place.

Getting ready to leave didn’t take long. We should only be gone maybe three nights, at most. And we might even spring for a room in one of the hotels in Corbin . . . providing Tarken was speaking to me by then. We’d get the farmers up to their waiting family, then we’d come right home. It was the most common run we made, and Martin and Tarken had cleared a road to there, mostly on an old paved one. They’d moved all the big rocks and trees, scouted out the likely ambush sites, and so on.

Corbin was over the border in New America, which was where almost all our cargo was bound. It was a large town with a number of places to stay, a garage for cars, a stable for horses, a post office, a good general store.

I’d worked for Tarken for two years now, maybe a bit over, and he’d been my man for four months. The first time we went to bed, he told me he’d been waiting until I was old enough.

I hadn’t even realized he was looking at me. I’m slow that way. But I’m quick with a gun, that’s what counts.

I would never have known I had a talent if my stepfather, Jackson, hadn’t taken me hunting with him when I was little. Jackson had seen me snatch a fly out of the air, he told me later, and he’d thought I had the quick hands and the instincts you needed to be a gunnie.

Jackson was right. The first time I held a rifle in my hands, I knew I’d found my calling. My mother didn’t like it, of course, but at least I could support myself—and be out in the open—doing something useful. People need protection.

I stuck a pair of pants and a shirt into my small leather bag, a pair of underpants, my toothbrush, and a comb. Packing was done. I’d fill my canteens before I left.

Next I cleaned my old 1873 Winchester, a lever action and a great rifle. It had been my grandfather’s. He’d called it Jackhammer, so I did, too. Jackson had given me matched Colt 1911s for close work, and those were already clean after my last target-shooting session out in the empty land around Segundo Mexia. I could fire twenty-seven bullets with all three, had extra magazines ready for the Colts. If I couldn’t bring our enemies down with that much firepower, our enemies had an army.

Galilee would bring her rifle, a Kra

g, since she was better at long shooting. I’d use the Winchester for closer work. She and Martin and Tarken all had pistols, too, though Tarken’s was less than a great tool.

Our truck and our firepower had worked for two years. We’d made this same run often.

Winchester in its sling over my back, pistols in their holsters and ready to go, two full canteens on one shoulder, my little leather bag with clothes and extra ammo on another; I was ready. I set off down the path to town.

People were coming home from work, and Chrissie was cooking on a grill outside her cabin, the smoke rising up and the smell of meat giving the air a nice tang. “Good shooting!” she called in her soft voice.

I nodded. I passed Rex Santino. “Easy death,” he said in his gruff way.

That’s what people wished gunnies. It made me feel good. I nodded back at him.

I didn’t want to walk down Main Street. There were too many people. One of them was my mother, who lived with Jackson in a real nice house just off Main. She didn’t like to see me leave on a job. That weakened me, too. I took a roundabout way to Martin’s house, which was situated in a bare dirt lot on the last street north in Segundo Mexia.

Martin’s chickens squawked in their pen as I came into the yard. He was strewing feed and smiling, just a little. He sure liked those stupid chickens. His neighbor’s kids would come in to feed them while Martin was gone, in exchange for eggs. We do a lot of barter in Segundo Mexia.

The setting sun struck Martin’s head with a golden glow. For the first time I noticed that Martin’s light hair had a lot of gray sprinkled in. I would pick my time to tease him about it.

Galilee wasn’t there yet. Tarken was putting the cans of extra gas on the bed of the truck, and he gave me a sideways smile, which froze when he realized my hair was gone. After a minute he closed his eyes, shook his head, and started back to working.

I’d hear about this later. I smiled. It was going to be fun.

Most of the cargo was sitting on the dirt of the yard or on Martin’s front porch. Two of the children were playing a game of hopscotch on the grid they’d drawn in the dirt. I nodded in their direction. I would talk to them when I couldn’t dodge it.

The sky went lower, the people on the porch shared out food among themselves, and I went into Martin’s kitchen and ate some bread and some dried fruit. I couldn’t handle meat before a job.

Galilee came in to sit with me, her Krag under her arm. She had on a gun belt with one pistol, maybe not as fine as my Colts—but the Colts were courtesy of Jackson, so I didn’t crow about them . . . much. Her hair stood out from her head like a huge black puff, and she was very skinny and dark. “My friend, you look a sight,” she said when she got a good look at me.

“Yeah. Like it?”

“Hell, no. You had the prettiest white-person hair I ever saw. Why’d you do it?”

“Tarken liked it too much.”

“So you decided you’d show him what was what.”

I shrugged. “More or less.”

“Girl. Sometimes I can tell you are so young.”

I didn’t know what that meant, so I didn’t answer. Only, I’d figured since Tarken spent so long running his fingers through my hair, straightening out each ringlet to watch it bounce back into curl, he’d better pay more attention to the girl whose scalp it grew on.

Galilee talked about other stuff. “Freedom built a chair for his little house,” she told me. Her son Freedom, who’d been born when Galilee was only fourteen, had moved out of his mom’s house when he left school and had gotten a job at the tannery. Now he’d built his own place. (And a chair.)

“He going to find a carpenter to apprentice to?” I couldn’t think of anyone around who’d be ready to hire. Bobby Saw already had a girl working for him.

Galilee lost some smile. “You know Freedom. That boy can’t stick with nothing. At least, not that he’s found yet.”

“That boy” and I were nearly the same age. At least Freedom had stuck with the tannery job. Though he didn’t like the work, it was steady money. He kept looking for something else, but nothing had suited him yet. Last time I’d seen him in a bar, he’d groused about it nonstop. He was lucky his girlfriend was sticking with him. Complaining is not attractive.

Martin came in to get a drink, kissed Galilee on the cheek as he went by. My eyebrows tried to climb into my hair, what was left of it. “Well,” I said when he’d gone back out. “You’re out in the open with it. When did that happen?”

She didn’t meet my eyes, but she was smiling again. “Just seemed like it was time. We’re getting along good, we want to spend more time together than we are. Ain’t no big thing.”

“Yet.”

“Yet,” she agreed.

“Lizbeth,” Tarken called from the yard.

“Time to work,” Galilee said, and we washed our plates and went to the outhouse and then to the truck. It was spring, days lengthening, and the sun didn’t want to give up the sky. There were no clouds, and I stood looking up, seeing the vastness above me, nothing between me and the hereafter. I had my place, standing here on this dirt.

Tarken gave us the nod. He and Martin were taking one last-minute look at the engine.

Galilee and I turned to the cargo. “Time to load up,” I called. “Sit in the center, looking out. Her and me, we got to stand up, her at the right side close to the back, me at the left side, closer to the front.” I pointed. I had to be clear. They were nervous.

Tarken would cover the straight-ahead from the passenger seat in the cab.

Martin had already arranged their bags against the sides, with two gaps left for me and Galilee just where we wanted them. The cargo had brought too much stuff, but they’d tried to pack it all in. They hated to leave things. This was all they had in the world.

The long, flat bed had sides Martin and Tarken had built, wooden uprights and horizontal planks, to hold everyone and everything in. Provided a little protection, too. And that gave Galilee and me a stable frame to lean on. We would go in last.

The families were standing, milling around, putting it off. “Load up,” I called with a little more push to my voice.

They obeyed. One man went in first, to help pull up the wives and the children, while the other remained on the ground to boost ’em up. The younger couple had a baby and a couple of littles, maybe six and four. The older couple had a girl, grown, and another girl about thirteen, and a boy, younger but not a baby. The men were brothers. They’d had farms side by side in south Texas, but when it had become Mexico, they had gradually been pushed out. Their older brother, they’d told Martin, was the one paying for their trip to New America. He was smarter; he’d sold his farm while he still had title to it, and bought land north of Corbin.

It seemed to take a long time, but finally they were all in. Galilee and I scrambled up and took our places. It was Galilee’s turn to talk.

“Hear me,” she said, and they all turned their faces to her. Dixie people wouldn’t have listened to a black woman, but these farmers did. She had the way and voice of someone who knew what she was doing. Her rifle spoke for her, too.

Galilee gave them the usual lecture about staying low and helping us keep watch. They all nodded, even the littles, scared just about shitless. Our prime worry was bandits, who wanted anything they could get: guns, goods, the human cargo. The guns and goods could be used or sold. The humans could be robbed or raped, and then sold to a bordello that wasn’t too choosy.

If the New America patrols stopped us, we’d be fine. People were legal cargo, and respectable people like this were even welcome in New America. But if bandits caught us, well, that was why Galilee and I were on duty. That was why the oldest brother had hired us to get the two families through the lawless land along the border between Texoma and New America.

Martin had climbed into the driver’s seat, and Tarken had take

n the shotgun position, as usual. I stretched forward to rap on the cab roof, letting them know she’d made the speech. The engine began to rumble, and we lurched out of the yard.

As we were leaving Segundo Mexia, I spotted Freedom walking by the side of the road and gave him a yell. At the sight of the truck, he took off his hat and waved it at his mother, who raised her hand in farewell.

“See you soon, son!” she called.

I could feel the farm people’s eyes going from the boy to his mother. The two were not exactly the same color. Galilee had gotten pregnant by the son of the landowner her parents worked for. Her parents had sacrificed to help Galilee run away. In Dixie, kids who didn’t look like their black mothers were in for a very hard time.

After many adventures, mostly bad, some good, Galilee had ended up in Segundo Mexia. But along the way, she’d learned to shoot. She had a skill. I trusted her with my life.

We were on a good part of the road, one that hadn’t been broken. There were still stretches around like that. My mother had told me that once almost all the roads were smooth, and that when they cracked, they got repaired. It sounded like a fancy dream. Since we were with the cargo, Galilee caught my eye and raised her rifle just a little. She was asking if I expected trouble.

Kind of to my own surprise, I nodded.

Galilee’s eyebrows went up. She was asking me why.

“Full moon,” I mouthed, with a tiny point upward.

Galilee shook her head, looking exasperated, her puff of hair flying around her face. She held up three fingers. Nothing had happened for the last three trips.

I held one hand palm up. Anybody’s guess, I was telling her. I didn’t want to jinx us.

Most likely, nothing would happen. We’d done this run dozens of times since I’d joined the crew. We’d had firefights, sure. We’d lost one crew member, an older guy named Solly. He’d taken a bullet to the stomach.

His had been the opposite of an easy death.

But we’d always gotten our cargo where they intended to go, except for two souls. One woman’s appendix had ruptured (at least that’s what we thought had happened), and she’d died in the middle of nowhere. One boy had been snakebit, and we couldn’t control snakes. So we had a good record.

Dead Ever After

Dead Ever After Grave Sight

Grave Sight Dead Until Dark

Dead Until Dark Real Murders

Real Murders Wolfsbane and Mistletoe

Wolfsbane and Mistletoe All the Little Liars

All the Little Liars Dead to the World

Dead to the World Club Dead

Club Dead Dead in the Family

Dead in the Family The Sookie Stackhouse Companion

The Sookie Stackhouse Companion All Together Dead

All Together Dead Dead as a Doornail

Dead as a Doornail Sleep Like a Baby

Sleep Like a Baby Night Shift

Night Shift A Touch of Dead

A Touch of Dead Living Dead in Dallas

Living Dead in Dallas Dead Reckoning

Dead Reckoning Deadlocked

Deadlocked Dead and Gone

Dead and Gone From Dead to Worse

From Dead to Worse Definitely Dead

Definitely Dead Last Scene Alive

Last Scene Alive Grave Secret

Grave Secret Three Bedrooms, One Corpse

Three Bedrooms, One Corpse The Russian Cage

The Russian Cage Shakespeares Counselor

Shakespeares Counselor Dead of Night

Dead of Night Shakespeares Trollop

Shakespeares Trollop One Word Answer

One Word Answer Shakespeares Champion

Shakespeares Champion Shakespeares Christmas

Shakespeares Christmas Shakespeares Landlord

Shakespeares Landlord Poppy Done to Death

Poppy Done to Death Dead Over Heels

Dead Over Heels An Ice Cold Grave

An Ice Cold Grave The Julius House

The Julius House Day Shift

Day Shift A Fool And His Honey

A Fool And His Honey A Longer Fall (Gunnie Rose)

A Longer Fall (Gunnie Rose) The Complete Sookie Stackhouse Stories (Sookie Stackhouse/True Blood)

The Complete Sookie Stackhouse Stories (Sookie Stackhouse/True Blood) Games Creatures Play

Games Creatures Play Death's Excellent Vacation

Death's Excellent Vacation (LB2) Shakespeare's Landlord

(LB2) Shakespeare's Landlord Dancers In The Dark - Night's Edge

Dancers In The Dark - Night's Edge Last Scene Alive at-7

Last Scene Alive at-7 Deadlocked: A Sookie Stackhouse Novel

Deadlocked: A Sookie Stackhouse Novel Dead But Not Forgotten

Dead But Not Forgotten (4/10) The Julius House

(4/10) The Julius House Dead Reckoning: A Sookie Stackhouse Novel

Dead Reckoning: A Sookie Stackhouse Novel A Touch of Dead (sookie stackhouse (southern vampire))

A Touch of Dead (sookie stackhouse (southern vampire)) (3T)Three Bedrooms, One Corpse

(3T)Three Bedrooms, One Corpse An Easy Death

An Easy Death A Secret Rage

A Secret Rage Many Bloody Returns

Many Bloody Returns![Harper Connelly [3] An Ice Cold Grave Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/25/harper_connelly_3_an_ice_cold_grave_preview.jpg) Harper Connelly [3] An Ice Cold Grave

Harper Connelly [3] An Ice Cold Grave Dancers in the Dark and Layla Steps Up

Dancers in the Dark and Layla Steps Up Small Kingdoms and Other Stories

Small Kingdoms and Other Stories Dead Ever After: A Sookie Stackhouse Novel

Dead Ever After: A Sookie Stackhouse Novel Dead in the Family ss-10

Dead in the Family ss-10 Sweet and Deadly aka Dead Dog

Sweet and Deadly aka Dead Dog An Easy Death (Gunnie Rose #1)

An Easy Death (Gunnie Rose #1) The Complete Sookie Stackhouse Stories

The Complete Sookie Stackhouse Stories Sookie Stackhouse 8-copy Boxed Set

Sookie Stackhouse 8-copy Boxed Set Sweet and Deadly

Sweet and Deadly Crimes by Moonlight

Crimes by Moonlight Dead Ever After: A True Blood Novel

Dead Ever After: A True Blood Novel Dead Ever After ss-13

Dead Ever After ss-13 After Dead

After Dead Dancers in the Dark

Dancers in the Dark (LB1) Shakespeare's Champion

(LB1) Shakespeare's Champion A Bone to Pick (Teagarden Mysteries,2)

A Bone to Pick (Teagarden Mysteries,2)