- Home

- Charlaine Harris

Many Bloody Returns Page 5

Many Bloody Returns Read online

Page 5

“Tonight, we talk about the future. And the past.”

Donika blinked. What did that mean? She would have asked but saw her mother stiffen. The woman’s eyes narrowed as she stared at her daughter’s bed.

“What is that?”

The girl turned. Specks of dirt, a small leaf, and a few pine needles were scattered at the foot of the bed, revealed when Donika had whipped the sheet off of her. A shiver went through her, some terrible combination of elation and guilt. She tried to stifle it as best she could.

“We cut through the woods to get downtown. I always go that way. I took off my sandals. I like going barefoot out there. It’s nice. It’s all…it’s wild.”

Donika couldn’t read the look on her mother’s face. If the woman suspected anything, she would have been angry or disappointed. Maybe those emotions were there—maybe Donika read her mother’s expression wrong—but the look in her eyes and the way she took a harsh little breath seemed like something else. Weird as it was, in that moment, Donika thought her mother seemed afraid.

The woman turned, all grim seriousness now. At Donika’s bedroom door she paused and looked back at her daughter, taking in the whole room—the guitar, the stereo, the records and posters, and the clothes she would never approve of that were hung from the back of her chair and over the end of her bed.

“No boys here while I’m gone. No boys, ’Nika.”

“I know, Ma. You think I’m stupid?”

“No,” her mother said, shaking her head, the sadness returning to her gaze. “No, you my baby girl, ’Nika. I don’t think you are stupid.”

With that, Qendressa left. Donika stood and listened to her go down the stairs and out the door. She heard the car start up outside and the sound of tires on the driveway, and then all was silent again except for the birds singing outside the window and the drone of a plane flying somewhere high above the house.

She wasn’t sure what her mother suspected or feared, didn’t know what had caused her to behave so oddly or why she’d freaked out so completely at the sight of the owl. But Donika had the feeling it was going to be a very weird birthday.

Gina couldn’t get the car, so the trip to the mall was off. Donika knew that she ought to have been bummed out, but she couldn’t muster up much disappointment. She’d be seeing her friends tomorrow night, and today she wasn’t in the mood to window-shop at the mall. The idea of wandering around Jordan Marsh or going to Orange Julius for a nasty cheese dog for lunch didn’t have much appeal. If it had been raining, maybe she would have felt differently. But the day was beautiful, and in truth, she wanted to be on her own for a while.

All kinds of different thoughts were swirling in her head, and she wanted to make sense of them if she could. Her mother’s strange behavior that morning troubled her, but she was still looking forward to the afternoon of them cooking together. The lamb in the fridge was fresh, not frozen. It had come from the butcher the day before. They’d put some music on—something her mother liked, the Carpenters, maybe, or Neil Diamond—and work side by side at the counter. Normally, that kind of music made Donika want to stick pencils in her eyes, but somehow with her mother whipping up the yogurt sauce for the lamb or slicing peppers as she hummed along, it seemed perfect.

At lunchtime she sat on the front porch with a glass of iced tea and a salami sandwich. A fly buzzed around the plate and then sat on the lip of her glass. Donika ignored it, more interested in the droplets of moisture that slid down the sides of the cup. She stared at them as she strummed her acoustic, singing a Harry Chapin song. Harry was one of the only musicians she and her mother could agree on.

“All my life’s a circle,” she sang softly, “sunrise and sundown.”

Her fingers kept playing, but she faltered with the words and then stopped singing altogether. Despite her concerns about her mother, she could not focus on anything for very long without her thoughts returning to the previous night.

Pausing for a moment in the song, she leaned over to pick up the iced tea, pressing the glass against the back of her neck. The icy condensation felt wonderful on her skin. Donika took a long sip, liking the sound the melting ice made as it clinked together. Then she set the glass down and grabbed half of the salami sandwich. All morning she had been ravenously hungry, yet when she’d eaten breakfast—Trix cereal, an indulgence left over from when she’d been very small—it hadn’t filled her at all. Later in the morning she’d had a nectarine and some grapes, and that hadn’t done anything for her either.

Now, even though she still felt as hungry as before—hungrier, in fact, if that was possible—the idea of eating her sandwich held very little appeal. She took an experimental bite, and then another. The salami tasted just as good as it always did, salty and a little spicy. But for some reason she simply did not want it.

She set the sandwich down and took another swig of iced tea to wash away the salt. Her fingers returned to the guitar and started playing chords she wasn’t even paying attention to. Whatever song she might be drawing from her instrument, it came from her subconscious. Her conscious mind was otherwise occupied.

“You’re a crazy girl,” she said aloud, and then she smiled. Talking to herself sort of proved the point, didn’t it? Her mother had always been a little crazy, and now Donika knew she shared the trait.

Her hunger didn’t come only from her stomach. Her whole body felt ravenous. Her skin tingled with the memory of Josh’s hands—on her belly, her breasts, the small of her back, the soft insides of her thighs—and of his kisses, which touched nearly all of the places his hands had gone.

She squeezed her legs together and trembled at the thought of stripping off her clothes, of running through the woods, and then Josh, his body outlined in moonlight, catching up to her. She’d felt, in those moments when she raced along the rutted path and he pursued her, as though she could spread her arms and take wing…as though she could have flown, and taken Josh with her.

Touching him, kissing him, that had been a little like flying.

“God,” she whispered to herself. “What’s wrong with you?”

Her fingers fumbled on the strings and she stopped playing, a sly smile touching her lips. Nothing was wrong with her. It all felt so amazingly good. How could anything be wrong with that?

But that was a lie. There was one thing wrong.

Her hunger. She yearned for Josh so badly that it gnawed at her insides. She wondered if her mother had seen it in her eyes this morning, had sensed it, had smelled it on her.

Donika needed to have his hands on her again, to taste his lips and the salty sweat on his fingers and his neck. She felt as though she couldn’t get enough of him. She wanted him completely, yearned to consume him, and the only way to do that was to do the one thing she promised herself she would not do.

She had to have him inside her.

Only that could satisfy her hunger.

Her certainty thrilled and terrified her all at once.

With the smell of cinnamon filling the kitchen, her mother leaned back in her chair, hands over her stomach as though she had some voluminous belly.

“I don’t think I ever eat again.”

Donika smiled, but it felt forced. They had followed the same recipes they had always used, brought over from Albania with her mother years ago, passed down for generations. Somehow, though, the food had tasted bland. Even the cinnamon had seemed stale in her mouth. The smell of dessert had been tantalizing, but its taste had not delivered on that promise. She had eaten as much as she did mainly because she hadn’t wanted to hurt her mother’s feelings. And the hunger remained.

How she could still feel hungry after such a meal—particularly when nothing seemed to taste good to her—Donika didn’t know. She chalked it up to hormones. Today was her sixteenth birthday. According to her mother, she had become a woman all of a sudden, like flipping a switch. She had never believed it really worked that way, but given the way she felt, maybe it did. Maybe that was exactly how it worked. Sh

e always craved chocolate right before she got her period—could have eaten gallons of ice cream if she’d given in—so this might be similar.

Or maybe it’s love. The thought skittered across her mind. She’d heard of people not being able to eat when they were in love. It occurred to her that this could be another symptom.

She tasted the idea on the back of her tongue. Did she love Josh?

Maybe.

She hungered for him, certainly. Longed for him. Could that be love? No. Donika had seen enough movies and read enough books to know that desire and love might not be mutually exclusive, but they weren’t the same thing either.

But desire like this? It hurts. It burns.

“—you listening to me, ’Nika?”

“What?” she asked, blinking.

Her mother studied her, concern etched upon her face. “You okay? You feel sick?”

“No. Sorry, Ma. Just tired, I guess.”

A lame excuse. She expected her mother to call her on it, maybe to make some insinuating comment about her walk in the woods the night before, about how maybe if she wasn’t always out talking to boys and running around with her friends, she wouldn’t be so tired. Her mother didn’t let her do very much, and she’d been hanging around the house all day playing guitar, and then cooking, but logic never stopped her mother from suspicion or judgment.

But Qendressa didn’t say anything like that.

“You like dinner, though, right?” she asked, and just then it seemed the most important question in the world to her. “Your sixteenth birthday the sweetest. You should be happy today. Celebrate.”

Donika felt such love for her mother then. Sometimes she became so angry and frustrated with the woman’s Old World traditions, but always she knew that beneath all of that lay nothing but adoration and worry, a mother’s constant companions. She thought she understood fairly well for a fifteen-year-old girl.

Sixteen, she reminded herself. Sixteen, today.

“I love you, Ma.”

They both seemed surprised she’d said it out loud. It had never been common to speak of love, though they both felt it all the time.

Her mother smiled, took a long, shuddering breath, and then began to cry. Donika stared at her in confusion. Qendressa turned her face away to hide her tears and raised a hand to forestall any questions.

After a moment, she wiped her eyes. “You all grown, now, ’Nika. Walk with me. Tonight, I tell you the story of how you were born.”

“What do you mean, how I was born?”

Her mother smiled and slid her chair back. It squeaked on the kitchen floor. “Walk with me,” she said as she stood. “In the woods. How you like. And maybe you learn why you like it so much.”

Donika got up, dropping her napkin on the table. Bewildered, she tried to make sense of her mother’s words and behavior, doing her best to push away the hunger inside her and to not think about the fact that Josh had said he’d be out on the corner later, waiting for her if she could manage to get out tonight.

Her mother took her hand. “Come.”

Together they left the house. The screen door slammed shut behind them as if in emphasis, the house happy to have them gone. The porch steps creaked underfoot. When her mother led her across the driveway toward the path, Donika hesitated a moment. The woods were hers. She might see other people in there, but something about going into the forest with her mother troubled her. Much as Donika loved her, she didn’t want to share.

“Ma,” she said, hesitating.

“It won’t take long,” Qendressa said. “But you need to know the story. Should have told you long time ago. I am selfish.”

Donika shook her head. What the hell was her mother talking about?

They walked into the trees. The summer sun had fallen low on the horizon. Soon dusk would arrive. For now, wan daylight still filtered through the thick trees, slanted and pale, shadows long.

“My mother, she knew things,” Qendressa began. Her grip on Donika’s hand tightened. “How to make two people love. How to heal sickness in body and heart. How to keep spirits away.”

Donika tried not to smile. This was what their big talk was about? Old World superstition?

“She was a witch?”

Her mother scowled. “Witch. Stupid word. She was smart. Clever woman. She used herbs and oils—”

“So she was the village wise woman or whatever,” Donika said, and it wasn’t a question this time. She thought it was kind of adorable the way her mother said herbs—with a hard H, like the man’s name. But this talk of potions and evil spirits made her impatient, too. “I get that she taught you all of that stuff, but how can you still believe it after living in America so long?”

Her mother stopped and pulled her hand away. “Will you be quiet and listen?”

The anguish in her mother’s voice stopped her cold. Donika had never heard her mother speak that way. The daylight had waned further and now the slices of sky that could be seen through the thatch of branches had grown a deeper blue. Not dusk yet, but soon. It seemed to be coming on fast.

“I’ll listen,” she said.

Her mother nodded, then turned and continued along the path. Donika watched the ground, stepped over roots and rocks. The woods were strangely quiet as the dusk approached, with the night birds and nocturnal animals not yet active and the other beasts of the forest already making their beds for the evening.

“She knew things, my mother. And so she taught me these things, just as I teach you to cook the old way. When I married, I made a good wife. Even then, I made money as a seamstress, just like now. But always my husband knew that one day the people in our town would start to come to me with their troubles the way they came to my mother. The ones who believed in superstitions.”

Donika couldn’t help but hear the admonishment in those words. Her mother wanted her to know she wasn’t the only one who still believed in such things.

“There were spirits there, in the hills and the forest. Always, there were spirits, some of them good and some terrible. Other things, too. Believe if you want, or don’t believe. But still I will tell you.

“I loved my husband. He had strong hands, but always gentle with me. Some people, they acted strange around my mother and me, but not him. He was so kind and smiled always, and when he laughed, all the women in our town wanted to take him home. But it was me he loved. We talked all the time about babies, about having a little boy to look just like him, or a little girl with my eyes.

“And then he dies. Such a stupid death. Fixing the roof, he slips and falls and breaks his neck. No herbs or oils could raise the dead. He was gone, Donika. Always his face lit up when he talked of babies and now he was dead and the worst part was there wouldn’t be any babies.”

The patches of sky visible up through the branches had turned indigo. The dusk had come on, and full darkness was only a heartbeat away. It had happened almost without Donika realizing, and now she heard rustling in the underbrush and in the branches above. A light breeze caressed her bare arms and legs and only then did she realize how warm she’d been.

She halted on the path and stared at her mother, eyes narrowed. “What are you talking about, Ma? What the hell are you…you had me.”

Qendressa slid her hands into the pockets of her skirt as though fighting the urge to reach out and take her daughter’s hand. Her features were lost in the gathering darkness.

“No, ’Nika. You came later.”

“How could I—“

“Hush now,” her mother said. “Just hush. You want to know. You need to know. So hush.”

Something shifted in the branches right above them and an owl hooted softly, sadly. Her mother glanced up sharply and scanned the trees as though the mournful cry of that night bird presented some threat.

Donika shook her head, more confused than ever. “Ma?”

Qendressa narrowed her eyes and took a step away from her daughter, casting herself in shadows again. “You know the word shtriga?”

>

“No.”

“No.” Her mother sighed, and the sound was enough to break Donika’s heart. “I was so much like you, ’Nika. Still very young, though already I was a widow. So many questions in my head. I walked in the forest always, cold and grieving and alone. I knew I had to have a baby, to be a mother. I would never love another, but a child I could love. I could have what my husband and I dreamed of…even if part of it is only a dream.

“One night I am in the forest, walking and dreaming, and I hear voices. Some men and some women. I hear a laugh, and I do not like the way it sounds, that laugh. So I walk quietly, slowly, and go through the trees, following the voices. I walked in the forest so much that I learned to make almost no noise at all. From the trees, I see them, two women and three men, all with no clothes. I felt ashamed to spy on them like that. I would have gone, but could not look away.

“They looked up at the sky and reached up to their mouths and they slipped off their skins, like they were only jackets. Inside were shtriga. They looked like owls, but they were not. I could not breathe and just watched, praying not to be seen. They flew away. I stood there until I could not hear the wings anymore and then I could breathe again.”

Qendressa paused. Donika realized that she had been holding her breath, just the way her mother had described. As the story unfolded, she had pictured it all in her mind, so simple to imagine because of all of the hours she had spent walking these woods by herself and because, just last night, she and Josh had been naked beneath the trees and the night sky. But this…her imagination could only go so far.

“Ma, you must have been dreaming. You said you were dreaming, right? You fell asleep. That couldn’t have been real.”

Her mother approached her, stepping into the moonlight, and Donika saw the tears streaking her face. Sorrow weighed on her and made her look like an old woman.

Dead Ever After

Dead Ever After Grave Sight

Grave Sight Dead Until Dark

Dead Until Dark Real Murders

Real Murders Wolfsbane and Mistletoe

Wolfsbane and Mistletoe All the Little Liars

All the Little Liars Dead to the World

Dead to the World Club Dead

Club Dead Dead in the Family

Dead in the Family The Sookie Stackhouse Companion

The Sookie Stackhouse Companion All Together Dead

All Together Dead Dead as a Doornail

Dead as a Doornail Sleep Like a Baby

Sleep Like a Baby Night Shift

Night Shift A Touch of Dead

A Touch of Dead Living Dead in Dallas

Living Dead in Dallas Dead Reckoning

Dead Reckoning Deadlocked

Deadlocked Dead and Gone

Dead and Gone From Dead to Worse

From Dead to Worse Definitely Dead

Definitely Dead Last Scene Alive

Last Scene Alive Grave Secret

Grave Secret Three Bedrooms, One Corpse

Three Bedrooms, One Corpse The Russian Cage

The Russian Cage Shakespeares Counselor

Shakespeares Counselor Dead of Night

Dead of Night Shakespeares Trollop

Shakespeares Trollop One Word Answer

One Word Answer Shakespeares Champion

Shakespeares Champion Shakespeares Christmas

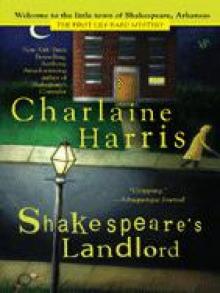

Shakespeares Christmas Shakespeares Landlord

Shakespeares Landlord Poppy Done to Death

Poppy Done to Death Dead Over Heels

Dead Over Heels An Ice Cold Grave

An Ice Cold Grave The Julius House

The Julius House Day Shift

Day Shift A Fool And His Honey

A Fool And His Honey A Longer Fall (Gunnie Rose)

A Longer Fall (Gunnie Rose) The Complete Sookie Stackhouse Stories (Sookie Stackhouse/True Blood)

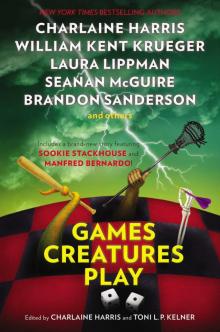

The Complete Sookie Stackhouse Stories (Sookie Stackhouse/True Blood) Games Creatures Play

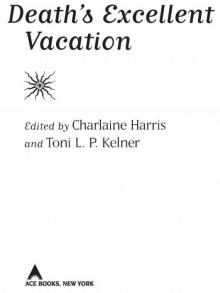

Games Creatures Play Death's Excellent Vacation

Death's Excellent Vacation (LB2) Shakespeare's Landlord

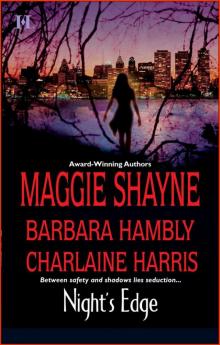

(LB2) Shakespeare's Landlord Dancers In The Dark - Night's Edge

Dancers In The Dark - Night's Edge Last Scene Alive at-7

Last Scene Alive at-7 Deadlocked: A Sookie Stackhouse Novel

Deadlocked: A Sookie Stackhouse Novel Dead But Not Forgotten

Dead But Not Forgotten (4/10) The Julius House

(4/10) The Julius House Dead Reckoning: A Sookie Stackhouse Novel

Dead Reckoning: A Sookie Stackhouse Novel A Touch of Dead (sookie stackhouse (southern vampire))

A Touch of Dead (sookie stackhouse (southern vampire)) (3T)Three Bedrooms, One Corpse

(3T)Three Bedrooms, One Corpse An Easy Death

An Easy Death A Secret Rage

A Secret Rage Many Bloody Returns

Many Bloody Returns![Harper Connelly [3] An Ice Cold Grave Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/25/harper_connelly_3_an_ice_cold_grave_preview.jpg) Harper Connelly [3] An Ice Cold Grave

Harper Connelly [3] An Ice Cold Grave Dancers in the Dark and Layla Steps Up

Dancers in the Dark and Layla Steps Up Small Kingdoms and Other Stories

Small Kingdoms and Other Stories Dead Ever After: A Sookie Stackhouse Novel

Dead Ever After: A Sookie Stackhouse Novel Dead in the Family ss-10

Dead in the Family ss-10 Sweet and Deadly aka Dead Dog

Sweet and Deadly aka Dead Dog An Easy Death (Gunnie Rose #1)

An Easy Death (Gunnie Rose #1) The Complete Sookie Stackhouse Stories

The Complete Sookie Stackhouse Stories Sookie Stackhouse 8-copy Boxed Set

Sookie Stackhouse 8-copy Boxed Set Sweet and Deadly

Sweet and Deadly Crimes by Moonlight

Crimes by Moonlight Dead Ever After: A True Blood Novel

Dead Ever After: A True Blood Novel Dead Ever After ss-13

Dead Ever After ss-13 After Dead

After Dead Dancers in the Dark

Dancers in the Dark (LB1) Shakespeare's Champion

(LB1) Shakespeare's Champion A Bone to Pick (Teagarden Mysteries,2)

A Bone to Pick (Teagarden Mysteries,2)