- Home

- Charlaine Harris

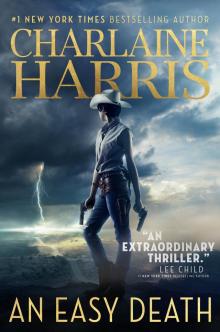

An Easy Death Page 6

An Easy Death Read online

Page 6

Maybe the man was looking a little harder, because he finally spoke. “We could come back in the morning,” he said, his voice quiet and even.

She half turned to him to say something, and he made a little hand gesture. She shut up. But she wasn’t used to taking hints. She was the boss.

“Any time is better than now. But most likely I won’t do whatever it is you want,” I said.

“Why?” She just couldn’t stop herself.

I picked the simplest reason. “I don’t want to have nothing to do with you,” I said. My mother would have given me the evil eye for bad grammar, but she wasn’t there and I was out of civil.

The woman opened her mouth again, but the younger man—he was maybe five years older than me—made a stop gesture with some force behind it. He must have had to quiet her a lot. “Tomorrow,” he said. “In the morning. We’ll be back then.”

The two of ’em left, passing me on the narrow path, not getting too close. Smart.

At last I was able to go in my own place and shut my own door. And I locked it. I needed to clean myself, but I’d run out of energy and will. I turned the faucet to find the water was running, so I washed my face and arms and took off my shoes before I fell onto the bed. If anyone else came by or knocked on the door, I didn’t know about it. I didn’t dream, that I remember.

Next morning I woke up looking forward, not back at the catastrophe on the road to Corbin. I was still alive. I had to plan what I’d do next. I had to make my living. I showered, scrubbing top to bottom. I fired up the woodstove. It was one of the last times I’d use it till fall; when the weather got hot, I cooked outside as much as I could. I made myself a big meal—cantaloupe, oatmeal, bacon. I felt much better after that. Much.

I was feeling dandy as I started on the dishes, but then I had one of the black moments when grief stabbed me unexpectedly. I had to fight back. Tarken, Martin, and Galilee were gone, but with honor. I had to be strong, all by myself. I made myself look out the window at the peace of the hillside. A vireo was in a bush nearby, and it was full of bird conversation. I took a deep breath in and out, and returned to my job.

As I scrubbed the oatmeal pan, I began singing a cowboy song about beautiful women, loyal men, and plains covered with flowers. My scratchy voice wouldn’t bother anyone, least of all the vireo. The little houses down the slope, they weren’t real close and this time of day they’d be empty, except for Chrissie and maybe her little boys. I’d realized it had to be Monday. The other grown-ups were at work; kids were at school with my mother if they were old enough. In Segundo Mexia everyone has something to do.

I’d stopped school at sixteen, which was a little old to still be in a classroom. Being my teacher and my mother, Mom had wanted to pass along as much knowledge as she could. It had been hard come by, since in the middle of her teacher training, when she herself was sixteen, she’d come up with me. My grandparents had watched me while Mom rode the bus to Little Bend to finish up. That bus hasn’t run in the past five years, but then it ran to the larger town and back daily. Grandma and Grandpa died when I was six, and my memories of them are sketchy: worn, lined faces, kind voices, stern discipline. The influenza took them, but they left behind a daughter who could support herself and her child.

My mom was a good teacher and a good mother. She did not believe that ignorance was bliss. She believed just the opposite. A lot of people didn’t want to talk about the past, because it was painful. But Mom thought I should know how things had gotten to be the way they were: the dead president, the dead vice president (influenza), the banks crashing, the drought, and the influenza . . . again.

The population had dropped, the government could not protect itself, and other countries had grabbed pieces of America.

“USA got big bites taken out of it: by Canada from the north, by Mexico from the south, and by the Holy Russian Empire from the west, where the Russian tsar settled when he fled his own country. To the east, the thirteen original colonies—all but Georgia—voted to form a bond with England, to keep from becoming part of Canada. They picked the name Britannia. The southern states banded together as Dixie. Georgia went with them.” She was pointing out the new countries on the map.

“So what about us?” I asked, looking at the old map. She pointed to the place where we lived. “Texas and Oklahoma and New Mexico and a bit of Colorado became Texoma, where we live. We live in Segundo Mexia, in Texoma. And this big area north of us, the plains, that’s New America.”

My mother also told me no one had ever heard of real magic until the Russian Christians left their own country, driven out by the godless people, to wander until they found a home on the West Coast. The movie industry welcomed them with open arms and pocketbooks, and when the crash came, the army the tsar had brought with him convinced California and Oregon to unite under him.

The Russian royal family had brought the grigoris with them, and the grigoris rejoiced in the open under the California sun. Now the Holy Russian Empire rules with lots of show and lots of mystic bullshit. It’s the only country in the world to openly admire magic.

And now there are all kinds of scum with a little bit of ability traveling around, putting on magic shows for the kiddies and selling “spells,” and one of them spelled my mom to hold still long enough to beget me, was what I had been thinking as my mother told me about the map. I figure maybe Mom had been thinking about the same topic.

The mistake one particular grigori scum had made was coming back to this area a second time. I smiled remembering that, but my happy minute was interrupted by a knock at my door. I dried my hands and reached for a gun. I opened the door real quick and stepped to the side.

I figured the odor of the soap I’d used—I’d found a scented bar in Corbin—had masked the grigori smell until they were real close. So much for my little talent.

The man and the woman looked the same as they had the afternoon before: tall, well nourished, well dressed, rested. Today they seemed a bit more worried.

Now that I was clean and had had a night’s sleep, and some food in my stomach, I felt I could deal with them.

I’d cleaned one of my Colts already. All the other firearms were spread out on the table, on sheets of old newspaper, along with everything I’d need: clean cotton rags, Hoppe’s, soft brushes. I was ready to work.

It was a good reminder to them.

“May we come in?” the woman asked. She didn’t sound Russian, something I’d been too tired to notice the day before. I figured her for a British import.

I jerked my head, and they stepped in. I pointed to the bench on one side of my table, and they sat. I had a stool and my back to the wall, so I could see out the door, which I left open. It was a mild morning, and I enjoyed the little breeze coming in.

I didn’t feel obliged to open the conversation. They were the ones who wanted something, not me.

I took apart Jackhammer first. My grandfather’s Winchester was utterly familiar to my hands. The feel of the cleaning rag, the brushes, the smell of the solvent, the care I was taking of the tools of my livelihood, all felt good and comfortable to me. Plus, I’d had a good look at the neglected bandit pistol. It seemed basically sound. If I put in some work, I’d get a good price for it.

“I’m Paulina Coopersmith,” the woman said. Yep, she had an accent. I’d only heard one like it at the movies. “Are all these guns yours?”

“Yes, they’re all mine,” I said. “I took most of ’em off the bandits who killed my crew.”

“You killed them all,” the man said.

I nodded. They didn’t have anything to say about that for a goodly bit of silence.

“I’m Ilya Savarov,” the man said finally. “Please call me Eli.” No doubt about him being Russian. He had a slight accent. He might make his name more American, but I was willing to bet he’d been in the ships that had brought the tsar and his family to the West Coast after their escape in 1918 from the godless Russians. Though this Eli had probably been a small child then, since he look

ed in his midtwenties now.

“Lizbeth Rose,” I said. But I realized they knew that. I almost told them not to call me anything.

Paulina and Eli and Lizbeth. We were pals now, for sure.

I finished the cleaning and reassembled and loaded Jackhammer. I set my cleaning stuff in a neat line back on a heavy pad.

“What do you want?” I said, satisfied with the job I’d done. I’d had my silence. Now it was time to get the conversation moving, so it could come to an end. So they would go.

I ran my hand down the walnut stock of Jackhammer one last time and laid it down. I made myself look directly at the grigoris. Paulina’s eyes were frosty blue and fixed on me with no very pleasant expression. Her accent was English. A lot of English magicians had migrated to California after hearing how friendly the HRE was to wizardry. They were tired of being ignored in their own country. Looked like the court had given ’em a big welcome.

“We need a guard and a guide,” Eli Savarov said. “We’re hoping you can be both.”

I looked at him directly. His eyes were green. I’d never seen that before, and it was striking. “For how long?” I said. I was going to turn them down, but not before I found out what they were doing in Segundo Mexia.

“For at least a week, maybe as long as three.”

“While you’re doing what?”

I began to clean the small parts of one of the bandit pistols, because I couldn’t just sit and look from one to another. It was necessary to concentrate on my hands, but I wasn’t so busy I didn’t catch the look they gave each other.

“We’re searching for a particular man,” Paulina said. She was picking her words one by one. “And the last trace we have of him is in this area.”

“Huh. No strangers here recently. You mean another one like you? A grigori?”

“We lost track of him some time ago,” Paulina said. “And he is a wizard, yes.” But her mouth twisted sour at giving him the title.

Eli said quietly, “He’s an embarrassment to us.”

“Yeah?” I didn’t want to meet someone they’d be proud of. “So, who is this guy?”

“A Russian-born wizard named Oleg Karkarov.”

Jackhammer was pointed at them before they could get to their feet.

“Get your hands up, now!” I said.

They made a great show of looking astonished and scared as they threw their hands up. You had to keep grigoris’ hands in front of your eyes; you couldn’t let them weave spells with their hands or reach for their vest pockets.

“What did we say?” Paulina said. She was pretty pissed off.

“You know he’s dead.”

But they didn’t. Even I had to admit they’d been taken by surprise.

“But—but where? When?” The man, Eli, stammered as he spoke. He looked . . . dismayed. As if his world had taken a big turn for the worse.

“Five miles away in Cactus Flats,” I said, not lowering Jackhammer. “Eight months ago. He your kin?”

“No,” said Paulina Coopersmith, disgusted at the very idea.

“How did he die?” Eli asked, right on her heels.

“Gunned down,” I said, glancing from one to another.

“On the head of the tsar,” Paulina said, “we did not know.” She was smart enough to see that their ignorance was real important to me.

I didn’t doubt her after that. Holy Russians, that was a serious oath to them. Alexei I was the symbol of everything they’d left behind, and their hope for the future.

Eli and Paulina were smart enough to keep their mouths shut while I thought. After a minute I laid down the rifle, but I kept it close.

Meeting the eyes of each grigori in turn, I nodded, so they could lower their hands. I wasn’t going to shoot them until I learned more. They wouldn’t spell me until they did the same.

I sank back onto my stool, but I didn’t relax. I continued to work on the filthy bandit pistol to keep my hands busy, because my fingers were all itchy to shoot. “You don’t need me to go on that big search of yours, now you know he’s dead,” I said. Maybe this would be the end of it.

In the silence after that, I calmed myself by thinking of what my hands were doing, and I planned what I’d do next. When I finished this pistol, which would take a long time, I would set to work on Tarken’s gun. Maybe I should give it to his boy. I was no favorite of the boy’s mother, Leisel, and she wouldn’t want to talk to me. But I was obliged to offer. And I had to talk to Freedom, Galilee’s son, who worked at the tannery, the one whose room I’d rented after he’d moved out of his mom’s.

The grigoris were murmuring back and forth in Russian, still being careful with their movements. It was a long conversation. I got a lot of work done.

All I learned was that they couldn’t read each other’s minds. That was good to know. Also interesting and of note was that Paulina had been in the HRE long enough to be fluent in Russian.

They stopped talking. They’d reached a conclusion.

“If Oleg is dead,” Eli said, “we need to find his brother.”

I was glad I was looking down, so they couldn’t read my face. I was thunderstruck. It was news to me that Oleg Karkarov had family. Now that I knew he did, I didn’t like it. My hands stilled for a moment. “Where is this brother likely to be?” I said cautiously.

“We know he was traveling with Oleg,” Eli said. Paulina nodded.

That was another bit of news I didn’t like.

“You need to talk to him? What about?”

“We need to find out if they were full brothers,” Paulina said. “If they were, we need his blood.”

I was able to look up at her with a genuine smile. “That’s my kind of quest,” I said.

Paulina and Eli both looked surprised that I knew an uncommon word. Fuck ’em. “My mom’s a teacher,” I said, before they could start trying to think of a nice way to ask.

“You’ve always lived in Segundo Mexia?” Eli said. I could feel he was trying to get me to relax, to like them, or at least to be at ease with them. Paulina didn’t seem to care about that, and I kind of respected her point of view.

“Yes,” I said, looking through the barrel of the pistol. My hands had been busy while the Russians talked. The barrel was clean as a whistle. I reassembled, loaded. Another job done. I still didn’t want the gun, but at least it was sellable.

The familiar smell of Hoppe’s oil was calming me. Instead of Tarken’s pistol, I picked up Galilee’s bolt-action Krag. It had bullets in it she’d never gotten to fire. That thought gave me a pang of grief. I put the Krag down and sat with my head bowed. I changed my mind about the Krag. I knew it was odd that I found it easier to face cleaning Tarken’s pistol than Galilee’s rifle. But I’d remembered Galilee’s big smile.

And that was wrong. There were two wizards in my home, and I should not be paying attention to anything but them.

Eli cleared his throat. He’d asked me a question. “Do your parents live here, too?” he said again. Eli was asking if they lived in Segundo Mexia. It was easy to see no one lived in this house with me.

“Why?” I made sure to meet both pairs of eyes, blue (Paulina) and green (Eli), so they’d see how serious I was about not answering questions about my family. And since I was looking up, I saw a shadow. Someone had crept up to the door, and by the time he stepped fully into sight, his pistol up, I had jumped to my feet, Jackhammer ready. Since I’d had to waste a second by standing, so my bullet would clear the grigoris’ heads, the other gunnie got off a shot. I felt my back hit the wall, and I slid down behind the stool.

“My God, it’s the Tatar,” Paulina was saying from far away.

“Was,” Eli said briefly from much closer. “Come over here.”

“She’s alive?”

“Yes.”

There was lots of shoving and clattering. They were moving my table and stool out of the way. I was lying against the wall. I caught a flicker of Eli’s face, broad and calm, but unhappy.

I could

hear someone yelling in the distance. Chrissie. Sure, gunfire would get even Chrissie’s attention. Glad she was here . . . I didn’t want these two in charge of me. . . .

My mother was sitting by me when I woke up. I was on my bed. She was sitting on the stool, which had been pushed over beside it.

“Good,” Mom said. “You’re conscious.” She sounded half-sad, half-angry.

“He was after them.” I couldn’t talk clear. But I wanted her to know it wasn’t my fault.

“Yeah,” Mom said. “He was a gunnie, like you. Josip something. Papers in his pocket.”

I’d heard of him. “Josip the Tatar. He had a big name.”

“Your name is bigger now. You killed him.” She turned her face away, and I could tell she was biting back the words, But that might have been you.

“I’m okay?” I said, after flexing my muscles a little bit. I was pretty sure I was, but I had to ask what injury I had incurred. I hadn’t exactly recovered from my bang on the head. Now my head felt bad again, sore and stiff.

“Bullet grazed your skull,” she said. “And since you just cut off all your hair, it was easy to see the wound. It just made a messy . . . crease. Those two wizards had patched you up by the time I got here.” Her face was all tight with trying to hold in stuff. “I have cleaned up all the blood,” she added between gritted teeth.

Head wounds bled like a bitch. “Them two still here?”

“Those two,” she said.

“Those two still here?”

“They’re sitting outside. Jackson came to have a look at you. He talked to them for a moment. He’d seen them at the Antelope.”

“You won’t believe what they . . .” I’d been going to warn her. But then I was out again. My next little moment of consciousness, I realized I’d been ready to tell my mom something she shouldn’t know about. I blessed the fact that I’d gone to sleep before I could. It went like that for what seemed like hours, a drifting time of sleep and dreams and hurting. I would be conscious just long enough to know where I was and that I’d been shot, and then I’d be out again.

When I woke up for real, my head was still hurting, though not as bad as I’d expected. Maybe I was just getting used to my head hurting. My mom was still there. Or there again.

Dead Ever After

Dead Ever After Grave Sight

Grave Sight Dead Until Dark

Dead Until Dark Real Murders

Real Murders Wolfsbane and Mistletoe

Wolfsbane and Mistletoe All the Little Liars

All the Little Liars Dead to the World

Dead to the World Club Dead

Club Dead Dead in the Family

Dead in the Family The Sookie Stackhouse Companion

The Sookie Stackhouse Companion All Together Dead

All Together Dead Dead as a Doornail

Dead as a Doornail Sleep Like a Baby

Sleep Like a Baby Night Shift

Night Shift A Touch of Dead

A Touch of Dead Living Dead in Dallas

Living Dead in Dallas Dead Reckoning

Dead Reckoning Deadlocked

Deadlocked Dead and Gone

Dead and Gone From Dead to Worse

From Dead to Worse Definitely Dead

Definitely Dead Last Scene Alive

Last Scene Alive Grave Secret

Grave Secret Three Bedrooms, One Corpse

Three Bedrooms, One Corpse The Russian Cage

The Russian Cage Shakespeares Counselor

Shakespeares Counselor Dead of Night

Dead of Night Shakespeares Trollop

Shakespeares Trollop One Word Answer

One Word Answer Shakespeares Champion

Shakespeares Champion Shakespeares Christmas

Shakespeares Christmas Shakespeares Landlord

Shakespeares Landlord Poppy Done to Death

Poppy Done to Death Dead Over Heels

Dead Over Heels An Ice Cold Grave

An Ice Cold Grave The Julius House

The Julius House Day Shift

Day Shift A Fool And His Honey

A Fool And His Honey A Longer Fall (Gunnie Rose)

A Longer Fall (Gunnie Rose) The Complete Sookie Stackhouse Stories (Sookie Stackhouse/True Blood)

The Complete Sookie Stackhouse Stories (Sookie Stackhouse/True Blood) Games Creatures Play

Games Creatures Play Death's Excellent Vacation

Death's Excellent Vacation (LB2) Shakespeare's Landlord

(LB2) Shakespeare's Landlord Dancers In The Dark - Night's Edge

Dancers In The Dark - Night's Edge Last Scene Alive at-7

Last Scene Alive at-7 Deadlocked: A Sookie Stackhouse Novel

Deadlocked: A Sookie Stackhouse Novel Dead But Not Forgotten

Dead But Not Forgotten (4/10) The Julius House

(4/10) The Julius House Dead Reckoning: A Sookie Stackhouse Novel

Dead Reckoning: A Sookie Stackhouse Novel A Touch of Dead (sookie stackhouse (southern vampire))

A Touch of Dead (sookie stackhouse (southern vampire)) (3T)Three Bedrooms, One Corpse

(3T)Three Bedrooms, One Corpse An Easy Death

An Easy Death A Secret Rage

A Secret Rage Many Bloody Returns

Many Bloody Returns![Harper Connelly [3] An Ice Cold Grave Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/25/harper_connelly_3_an_ice_cold_grave_preview.jpg) Harper Connelly [3] An Ice Cold Grave

Harper Connelly [3] An Ice Cold Grave Dancers in the Dark and Layla Steps Up

Dancers in the Dark and Layla Steps Up Small Kingdoms and Other Stories

Small Kingdoms and Other Stories Dead Ever After: A Sookie Stackhouse Novel

Dead Ever After: A Sookie Stackhouse Novel Dead in the Family ss-10

Dead in the Family ss-10 Sweet and Deadly aka Dead Dog

Sweet and Deadly aka Dead Dog An Easy Death (Gunnie Rose #1)

An Easy Death (Gunnie Rose #1) The Complete Sookie Stackhouse Stories

The Complete Sookie Stackhouse Stories Sookie Stackhouse 8-copy Boxed Set

Sookie Stackhouse 8-copy Boxed Set Sweet and Deadly

Sweet and Deadly Crimes by Moonlight

Crimes by Moonlight Dead Ever After: A True Blood Novel

Dead Ever After: A True Blood Novel Dead Ever After ss-13

Dead Ever After ss-13 After Dead

After Dead Dancers in the Dark

Dancers in the Dark (LB1) Shakespeare's Champion

(LB1) Shakespeare's Champion A Bone to Pick (Teagarden Mysteries,2)

A Bone to Pick (Teagarden Mysteries,2)