- Home

- Charlaine Harris

Death's Excellent Vacation Page 6

Death's Excellent Vacation Read online

Page 6

She’s shouting at him. I can get old, he thinks. I can be old like a bitter old man. I can be bitter.

But I can’t be an old man.

I can’t be a man at all.

The kids are looking out the window at him, adoring, hoping for miracles.

“Who are you?” he says. “What right have you to ask me to do anything? You and they will be dead by the time I’ve had my lunch. You want me to do anything for you? You want me to care about you? That’s going to hurt me, and it won’t help you or them.”

“You have no idea what you can do, do you?”

He knows what he can’t do.

“Then I’ve given you your wish, Green Man,” she says. “You are dead. You care about nothing. You are a rock. A stone. An old man fishing until the end of the world.”

I can’t, he thinks. I don’t have the talent for that either.

“Then let’s try something else,” she says.

SHE could book a flight on her magic phone, but she doesn’t. She makes him zip them across the Atlantic in a glowing green saucer a hundred feet long. She tells him he can make it invisible to radar and infrared and light, can’t he? The kids scream and giggle and bounce around the inside of the flying saucer and ask him to turn off the gravity inside, which he does. The kids fly. He’s a terrified protector, afraid of the villagers, helping them from a distance, a watchdog and not a man. He is bony ribs around the kids’ beating hearts. He feels like someone in an airplane, speeding along too fast, cradled by something he can’t control.

They land on the Mars-rocky shore of the loch, between the pines and the peaty water, Lan and Green and a luminous flying saucer full of giggling, flying teenage Japanese shape-changers. “Make it a submarine now,” the kids tell him. He thinks about recirculators, scrubbers; he pushes molecules around. They sink into the brown darkness like into moving loam.

“Can you—” Lan says.

But he holds up his hand. He has been here.

Ice fishing: the seldom-seen, magical moment when the water under the ice is clear, when the fish can see light from a distance. When they gather. When, in the light, the fisherman sees muscular dark bodies turning. When the fish looks at the fisherman, curious, and the fisherman looks at the fish.

What can you do? Who are you?

He does like he did with the dirt on the floor, like at Lake Musky seining for the kids, but tinier, tiny. He sends out into the water nets that are no stronger than metaphors, trawling for the smallest pieces of drowned bark and leaf, gathering them together, dodging around any fish or eel or water snake. He thinks about Brownian motion. Why did they need Atom’s light? The water clears. The water clears, leaving worms and little fish wriggling, surprised. The darkness recedes around them; a bigger fish bullets by, mouth open, and the small fry streak for safety in the blackness below them. Green globes light around the kids, and around them the fish gather, as if they are all in one great dark place under the ice together, with one flashlight to draw them.

The kitten-girl gives a little breathy scream.

Out of the blackness, out of the depths, She comes. She strikes at the glow, but Green thinks slipperiness and the ball that holds them spins past her teeth. She mouths a man-sized fish and flips her body round, whirls around them, thrashing, stretching out her neck, trying to catch them. She is too big to see whole. Riffles of gills, a great round flat eye like a target, scarred scales.

He plays her. Green is the worm; Green is the net, the line, the hook. The great She-Fish worries at the green ball- light, her teeth an inch away from them, and he and Lan and the kids bounce away from her. She wraps her long neck and tail around them. He feints and slides away.

And then suddenly it is a dance. He knows what she wants. He morphs the ball in which they all float into a mirror-monster of her, a ghost monster of green and light. She rears back. He shapes the green fish to match her motion. And for a moment the two of them hang there, in the water clear as glass, a monster fish like ebony and a monster fish like emerald, and she is still, still, still, and she reaches out her long neck, sniffing, opening her mouth to taste the water with her tongue, tilting her head so she sees him out of one enormous eye. Are you like me, her outstretched neck says, her tongue licks, and Green’s heart beats loud in his ears, Are you like me?

But she throws her head back with a cry of loneliness and disappears into the deep.

When they are back on dry land, the kids say nothing. They stand on the rocky shore, each of them alone for a minute. Then the boy goes from one to the other, touching them on the shoulder, bringing them together into a protective hug. They reach out for the two older men, for Lan. She reaches out for him. Green stands with them, embracing them and embraced.

Tonight he has done new things. Of all of them, that silent lonely hug is the hardest, and it’s what he will remember, that and Nessie’s tongue tasting the green monster made of force and silt, hoping she could find something like herself.

HE takes everyone back to Japan in his invisible force-field UFO. They’re quiet on the trip. Over Japan, the trees are pink and green with springtime. At the big Tokyo train station, the kids and the older men shake hands with him and Lan. Then the Japanese Talents wander away, down escalators. The station is a big mall, open in the center. Green and Lan can still see the group, past the escalator, two levels below them. The kids stand in front of a game store, huddling together.

“Guess they thought they’d be happier when the heroics happened,” Green says. “Guess they thought they’d figure something out.”

“They’ve seen monsters,” Lan says.

He nods.

“We went fishing,” he says. “Four of us. We were so jazzed about being Talents. That was the age of Talents. We thought we had it made. We were kings of the world. We were like each other. But Atom got sick, Astounding was going to get himself blown up someday and he did, I stole my wife from Iguana and pretended to be human. We went fishing and we caught loneliness. I can’t help the kids, Lan. Badgers and cats don’t live more than a few years. Someday there’ll be only one of them left. And it’ll see something it thinks is like itself or its friends, but the smell will be wrong and the taste will be wrong, and it’ll know it’s the only one of itself in the world. Being the one there’s only one of, that’s being a monster.”

“I’ll buy you a present,” Lan says.

She makes him wait outside a shop full of statues of every description, from Buddha to the Virgin Mary. Here in Planet Tokyo you buy Buddhas in a train station. She comes out with a little box. Not far away from them there’s something like a food court with little tables. They take a table with pink plastic flowers embedded in its top. “Open your present now.” She goes away and comes back with two drinks, something chewy and sweet with barley in it.

Green’s present is eight little plastic statues in a row on a plastic base.

“The Eight Immortals.” She touches their small heads one by one. “Immortal Woman He, whose lotus flower gives health. Royal Uncle Cao, whose jade tablet purifies the world. Iron-Crutch Li, who protects the needy.” She takes the next one off the stand, a slim Chinese boy or girl with a woven basket and a flute, and stands it by her purse. Through the woven material of the purse he can see the outline of that long flute. “Lu Dongbin, whose sword dispels evil spirits. Philosopher Han Xiang, whose flute gives life. Elder Zhang Guo, master of clowns, winemaking, and Qigong kung fu. Zhongli Quan, whose fan revives the dead.”

Green picks up the statue with the basket and flute, and looks a question at her.

“Immortal Woman runs a health food store in New Jersey. The Philosopher and Quan are dead, I think. The Philosopher’s flute came to me in the mail one day. I saw Zhang Guo on the beach in Monterey but he wouldn’t talk to me. Lu, Li, Cao, I don’t know. Immortal Woman frightens me most. She didn’t want to be a monster. She wanted friends and neighbors. She made herself forget she was immortal. I go in there once a year or so, and she says nothing but

trivial things, How do you like those Dodgers? She never stops talking. She bores everyone and forgets to charge for newspapers. But she isn’t a monster.”

“You want to be lonely?” Green says. “You want to be alone?”

She touches the statue he has picked up, which means she touches his hand. “Lan Caixe. The shape-changer, the mysterious one. The minstrel whose songs foretell the future. No,” Lan says, “I didn’t want to be a monster. So I made other shape-changers, and I thought they would be like me.”

“Yeah,” Green says.

“Which made me a monster.”

He doesn’t move his hand, though he agrees with her. Her fingers stay lightly on his, ready to be rejected.

“I thought you could help,” she says. “You would make me not a monster anymore.”

“Wish I could have.” Still their hands touch, in midair, but he doesn’t pull away, until it’s awkward, or meaningful, or something, but neither of them pulls away.

“What are we if we aren’t humans or heroes? Are we always monsters?” she asks.

No. We are, he thinks. We just are.

Immortal? Enduring. Like a rock, like an old man fishing—?

“Organized, maybe,” he says to her.

“Not very.” But she smiles.

“You more than me.”

“It’s a talent.”

The kids could use help. Not that he can give it. He has failed at being a Protector and failed at being a man. But maybe she can think of something he can do. Maybe together they can—

He wonders if she’s foreseeing he’ll think that.

He wonders what she’s foreseeing.

That might bother him, her foreseeing him.

“I owe them,” she says. “Thanks.”

But maybe it won’t bother him much.

“S’pose we go back to my place; we can have some coffee and talk about stuff.”

“You don’t have any tea?” says his red-haired Chinese immortal hopefully.

Nope, he’s about to say; but here he is in Shinjuku Station, in Japan, on another planet, and it is spring. Nothing will bring back Mutti and Dadu, nothing will bring back his lost wife or his old friends. Even if Lan is one of the Eight Immortals, there are no guarantees. And nothing will make him a man.

But perhaps to be superhuman you need to have been human once, and failed.

Here is what I’d say to you, he thinks to those little Japanese kids he will probably meet again, here’s the advice I’d give. You little bits of frost, you falling leaves, you mortals? You’re doing the important thing right. Keep hold of each other as long as you can. Hug each other and hang around together.

Nothing lasts forever. But Atom and Astounding and the Iguana and me?

We had a great time fishing.

“This is Japan. I bet we can buy us some tea.”

One for the Money

JEANIENE FROST

Jeaniene Frost lives with her husband and their very spoiled dog in Florida. Although not a vampire herself, she confesses to having pale skin, wearing a lot of black, and sleeping in late whenever possible. And although she can’t see ghosts, she loves to walk through old cemeteries. Jeaniene also loves poetry and animals but fears children and hates to cook. She is currently at work on the next novel in her bestselling Night Huntress series.

One

I squinted in the morning sunlight. At this hour, I should have been in bed, but thanks to my uncle Don, I was traipsing across the NCSU campus instead. I strode up to Harrelson Hall, then climbed to the third floor to the class I was looking for. When I walked in, most of the students ignored me, either chatting with each other or rifling through their bags as they waited for class to start. The room had stadium-style seating, with the entrance down by the professor’s lectern. My lower vantage point gave me the same sweeping view of the students the professor would have. I scanned every face, seeking the one that matched the jpeg I’d been sent. No, no, no . . . ah. There you are.

A pretty blonde stared back at me with barely concealed suspicion. I smiled in a friendly way and threaded up the aisle toward her. My smile didn’t soothe her; she flicked her gaze around the room as if debating whether to make a run for it.

Tammy Winslow, I thought coolly. You should be scared, because you’re worth a lot of money dead.

The air felt charged with invisible currents moments before a ghost burst into the room. Of course, I was the only one who could see him.

“Trouble,” the ghost said.

Sounds of heavy footsteps came down the hall while the air thickened with greater supernatural energy.

So much for doing this the quiet way.

“Get Bones,” I told the ghost. “Tell him to be ready at the window.”

That turned a few heads, but I didn’t care about my college-student ruse anymore. I had to get those people out of here.

“I’ve got a bomb,” I called out loudly. “If you don’t want to die, get out now.”

Several kids gasped. A few snickered, not sure if I was kidding, but no one ran for the door. The footsteps coming down the hall got closer.

“Get out now,” I snarled, pulling my gun out of its hidden holster and waving it.

No one waited to see if I was kidding anymore. Scrambling ensued as the students ran for the door. I held on to my gun, shouting at everyone to stay away from me, relieved to see the room emptying. But when Tammy tried to dart away, I grabbed her.

A man barreled through the door, knocking the panicked deluge of students aside as if they were weightless. I shoved Tammy away and whipped out three of the silver knives that I had strapped to my legs under my skirt, waiting until no one was in front of him before flinging them at the charging figure.

He didn’t try to dodge my blades, and nothing happened when they landed in his chest. A ghoul, great. Silver through the heart did nothing to ghouls; I’d have to take his head off to kill him. Where was a big sword when I needed one?

I didn’t bother with more knives, but launched myself at the ghoul, bear-hugging him. He pounded at my sides, smashing my ribs as he tried to shake me off. Pain flared in me, but I didn’t let go. If I were human, the punishment from his fists would have killed me, but I was a full vampire now, so my broken bones healed almost instantly.

I managed to put the gun’s muzzle to the ghoul’s temple and pulled the trigger.

Screams erupted from the few kids still left in the room. I ignored them and kept pumping bullets into the ghoul’s head. The bullets wouldn’t kill him, but they did a lot of damage. His head was in oozing pieces when I let go.

Tammy tried to run past me, but I was faster, knocking over desks in my way as I grabbed her. Scraping sounds let me know the ghoul was crawling toward us, his head healing with every second. I hopped over the desks, yanking Tammy along with me, and pulled out my largest knife from under my sleeve. With a hard swipe, I skewered the ghoul’s neck.

The ghost appeared in the window, followed by another surge of energy coming from the same direction. Time to go.

Tammy screamed as she fought me, trying to break my hold on her. “I’m not going to hurt you,” I said. “Fabian.” I glanced at the ghost. “Hold on.”

He wrapped his spectral hands around my shoulders. Tammy wasn’t as trusting. She kept screaming and kicking.

I ignored that and ran right at the window. Tammy shrieked as we smashed through it with a hail of glass. Since her classroom had been on the third floor, we didn’t have a long hang time before something collided with us, propelling us straight upward. Tammy’s screams rose to a terrified crescendo as we rocketed up at an incredible speed.

“Somebody help me!” she shrieked.

The vampire who’d caught us adjusted his grip, flying me, Tammy, and the hitchhiking ghost toward our destination at the far edge of campus.

“Somebody has,” he replied, English accent discernible even above Tammy’s screams.

THE Hummer was equipped with bulletproof windows, a reinf

orced frame, and a backseat that couldn’t be opened from the inside. Tammy found that out when she tried to escape as soon as we’d thrown her in and sped off. Then she’d shrieked for another ten minutes, ignoring my repeated statements that we weren’t going to hurt her. Finally, she calmed down enough to ask questions.

“You shot that guy in the head.” Her eyes were wide. “But that didn’t kill him. How is that possible?”

I could lie. Or I could use the power in my gaze to make her believe she hadn’t seen anything unusual. But it was her life on the line, so she deserved the truth.

“He wasn’t human.”

Even after what she’d seen, her first reaction was denial. “What kind of bullshit is that? Did my cousin send you?”

“If he’d sent us, you’d be dead now,” Bones said, not taking his attention off the road. “We’re your protection.”

I knew the exact moment Tammy got a good look at the vampire who’d snatched us out of thin air, because she stared. Her scent changed, too. That former reek of terror became a more perfumed fragrance as she checked out his high cheekbones, dark hair, ripped physique, and sinfully gorgeous profile.

Young, old, alive, undead, doesn’t matter, I thought ruefully. When Bones is around, women go into heat.

But Tammy had just been through a very traumatic experience, so I ignored the vampire territorialism that made me want to grab Bones and snap, “Mine!” Instead, I handed her a pack of wet wipes.

She looked at them with an incredulous expression. “What do you expect me to do with these?”

“Nothing works better to wipe off blood, believe me,” I said, showing her my newly cleaned arms.

Tammy looked at them, at me, and at Bones. “What is going on?”

Dead Ever After

Dead Ever After Grave Sight

Grave Sight Dead Until Dark

Dead Until Dark Real Murders

Real Murders Wolfsbane and Mistletoe

Wolfsbane and Mistletoe All the Little Liars

All the Little Liars Dead to the World

Dead to the World Club Dead

Club Dead Dead in the Family

Dead in the Family The Sookie Stackhouse Companion

The Sookie Stackhouse Companion All Together Dead

All Together Dead Dead as a Doornail

Dead as a Doornail Sleep Like a Baby

Sleep Like a Baby Night Shift

Night Shift A Touch of Dead

A Touch of Dead Living Dead in Dallas

Living Dead in Dallas Dead Reckoning

Dead Reckoning Deadlocked

Deadlocked Dead and Gone

Dead and Gone From Dead to Worse

From Dead to Worse Definitely Dead

Definitely Dead Last Scene Alive

Last Scene Alive Grave Secret

Grave Secret Three Bedrooms, One Corpse

Three Bedrooms, One Corpse The Russian Cage

The Russian Cage Shakespeares Counselor

Shakespeares Counselor Dead of Night

Dead of Night Shakespeares Trollop

Shakespeares Trollop One Word Answer

One Word Answer Shakespeares Champion

Shakespeares Champion Shakespeares Christmas

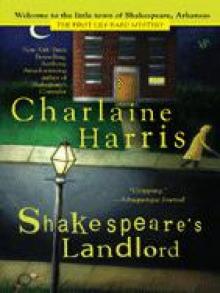

Shakespeares Christmas Shakespeares Landlord

Shakespeares Landlord Poppy Done to Death

Poppy Done to Death Dead Over Heels

Dead Over Heels An Ice Cold Grave

An Ice Cold Grave The Julius House

The Julius House Day Shift

Day Shift A Fool And His Honey

A Fool And His Honey A Longer Fall (Gunnie Rose)

A Longer Fall (Gunnie Rose) The Complete Sookie Stackhouse Stories (Sookie Stackhouse/True Blood)

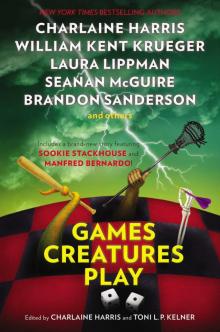

The Complete Sookie Stackhouse Stories (Sookie Stackhouse/True Blood) Games Creatures Play

Games Creatures Play Death's Excellent Vacation

Death's Excellent Vacation (LB2) Shakespeare's Landlord

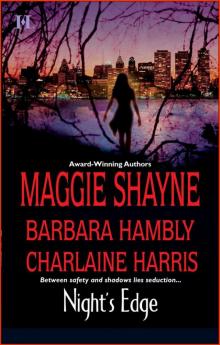

(LB2) Shakespeare's Landlord Dancers In The Dark - Night's Edge

Dancers In The Dark - Night's Edge Last Scene Alive at-7

Last Scene Alive at-7 Deadlocked: A Sookie Stackhouse Novel

Deadlocked: A Sookie Stackhouse Novel Dead But Not Forgotten

Dead But Not Forgotten (4/10) The Julius House

(4/10) The Julius House Dead Reckoning: A Sookie Stackhouse Novel

Dead Reckoning: A Sookie Stackhouse Novel A Touch of Dead (sookie stackhouse (southern vampire))

A Touch of Dead (sookie stackhouse (southern vampire)) (3T)Three Bedrooms, One Corpse

(3T)Three Bedrooms, One Corpse An Easy Death

An Easy Death A Secret Rage

A Secret Rage Many Bloody Returns

Many Bloody Returns![Harper Connelly [3] An Ice Cold Grave Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/25/harper_connelly_3_an_ice_cold_grave_preview.jpg) Harper Connelly [3] An Ice Cold Grave

Harper Connelly [3] An Ice Cold Grave Dancers in the Dark and Layla Steps Up

Dancers in the Dark and Layla Steps Up Small Kingdoms and Other Stories

Small Kingdoms and Other Stories Dead Ever After: A Sookie Stackhouse Novel

Dead Ever After: A Sookie Stackhouse Novel Dead in the Family ss-10

Dead in the Family ss-10 Sweet and Deadly aka Dead Dog

Sweet and Deadly aka Dead Dog An Easy Death (Gunnie Rose #1)

An Easy Death (Gunnie Rose #1) The Complete Sookie Stackhouse Stories

The Complete Sookie Stackhouse Stories Sookie Stackhouse 8-copy Boxed Set

Sookie Stackhouse 8-copy Boxed Set Sweet and Deadly

Sweet and Deadly Crimes by Moonlight

Crimes by Moonlight Dead Ever After: A True Blood Novel

Dead Ever After: A True Blood Novel Dead Ever After ss-13

Dead Ever After ss-13 After Dead

After Dead Dancers in the Dark

Dancers in the Dark (LB1) Shakespeare's Champion

(LB1) Shakespeare's Champion A Bone to Pick (Teagarden Mysteries,2)

A Bone to Pick (Teagarden Mysteries,2)