- Home

- Charlaine Harris

A Secret Rage Page 9

A Secret Rage Read online

Page 9

‘You haven’t exactly had time,’ she said briskly. ‘Now, I think you ought to try to walk around some, so you won’t get stiff. The doctor wants to see you again this afternoon and take some x-rays of your ribs, just to check, and the police want to take pictures. We have to make a dentist appointment, too.’

I didn’t want to see anyone at all. I didn’t want my face recorded. I wanted to stay in the house. I wanted to get dressed and study. I wanted to do anything normal, anything routine, to keep from remembering the night before. But there was my brave speech to Elaine Houghton to live up to. I rubbed my forehead. There was a gap, I thought, between my intentions and my desires. There was more to face now than I’d faced the night before, when I had seen the thread of my life held in someone else’s hands.

The thread of my life was in my own hands again. I was alive to face those problems.

Gratitude raced through me for the precious life I had kept. I looked at the sunlight drifting through the curtains. I looked over at my books, piled on the desk on the other side of the room. I was deeply grateful to God that I would be able to open those books again.

I would pay a price for my life. I might lose some of the friends I’d just begun making, lose them in a welter of embarrassment and misunderstanding. But what did that matter if I was still alive?

At that second, I felt I would never lose the wonderful awareness that everything was new for me. I had thought my eyes would never see the world again. I decided I would never take for granted any action my live hands could perform. I looked at those hands, saw the veins still working to purify my still-circulating blood, flexed the muscles that worked so miraculously. I watched the bones move under my skin.

That glory, that beauty, didn’t ebb, even when I stood painfully, even when Cully helped me hobble out to the kitchen for the most delicious bowl of Campbell’s chicken noodle I’d ever tasted.

* * * *

Cully explained something to me later that day.

‘I started to tell you twice, once the day I first saw you and again when we were on our way back from the landfill. I have a friend on the police force, a guy I used to hang around with in the summers.’ Cully, like Mimi, had gone away to school. ‘He told me that when Heidi Edmonds got raped, the police thought it was a fluke. A transient, or maybe a boyfriend no one knew about who got carried away. But then they began hearing rumors that another woman had been raped and just couldn’t report it. And then another.

‘So, my friend figured it wasn’t a fluke. There really was a rapist in town. He got the police chief to come to me, with the idea I could give them some directions to look in. But there wasn’t anything I could tell them that was helpful. I started to warn you, twice. But both times I decided I’d just frighten you more than I’d get you to be alert. I figured you’d be on your toes anyway, since you’d lived in New York. And after Barbara got raped, I didn’t think I needed to say anything.’

It wouldn’t have made any difference, and I told him so. His face relaxed. ‘Cully, even if I’d locked my window, which I only might have done if you’d warned me, the police told Mimi the locks on those windows are so old a ten-year-old could get in. Don’t ever think of it again.’

I hope he didn’t. I never did.

* * * *

Sunday was another out-of-kilter day. After the bustle and appointments of the day before, it felt empty. Empty for me, anyway; Mimi was kept busy answering the telephone. No one, apparently, wanted to come by, because they weren’t sure what shape I was in. But they wanted to express concern. Mimi said most of the callers sounded frightened.

I hunched on the couch, hearing the reassuring murmur of Mimi’s voice in the background. I stared in front of me with an awful emptiness echoing through my whole body. Emma lay open on my lap, but I never turned a page. This crisis was too evil for gentle Jane.

I had always been healthy, so physical pain was new to me, and shocking. I couldn’t move without a reminder of what had happened to me, though it was never far enough from my thoughts to make that necessary. The rape happened to me over and over again, that Sunday.

I discovered many things.

I discovered that pain requiring vengeance is very different from accepted pain. The misery of my father’s death now seemed equivalent to the coldest grimmest day of winter, perhaps after an ice storm, when every forward step is shaky. But this pain had pinned me in the middle of the forehead, branding me with a sizzling V for victim.

I discovered I wanted to know his face. I wanted to seize that face in my hands and rip it, cause pain, draw blood. I wanted to say, ‘See! This is what you did to me!’ I wanted to hang him naked and conscious in a public place, and say again, ‘See! This is what you did to me!’ And I would never be able to do it.

But still I wanted that face, and I swore to find it. I swore before I went into the bathroom to look in the mirror for the first time.

I discovered then that my face was finally my own. I would never see or think of it as a separate thing again. I would also never again think of myself as beautiful. Even after the skin healed, even when the bruises faded.

I wanted to know his face.

* * * *

I went back to classes on Monday. It was the hardest thing I’d ever done.

Two days had started the healing but made the discoloration of the bruises more lurid. At least my clothes covered my ribs and stomach. If any student at Houghton College, any resident of Knolls, had wondered who the rape victim was, they would wonder no longer.

That was why I had been beaten; so everyone would know.

As I left the shelter of the house, it occurred to me that any man I saw, any man I knew, might be the one who’d done this to me. He could examine his handiwork; he would be pleased with what he’d done to my face.

And he might be furious that I was apparently going to go on with my life. As that new fear occurred to me, my courage faltered. I clasped my books closer to my chest, as if they could protect me. My feet dragged. I was desperately tempted to turn back to the house, to hide myself from his eyes.

‘No no no,’ I swore out loud, and slapped my chest with the books. Going back to the house today could easily – so easily – be the first step toward shutting myself in it for the rest of my life. I would not, could not, do it. That would give him what he wanted, on a platter. I’d felt that in his rage.

But more than that I did not know. Even under a requestioning by the tired detectives, I couldn’t think of anything tangible to tell them, except that the man was white, solidly built . . . his weight had not been light on me; don’t think don’t think . . . and he had said he might come back.

‘Common threat. Don’t worry about it. They never do,’ Detective Tendall had reassured me. He hadn’t looked at me as he said it.

Never? Tendall was fudging just a wee bit, I decided. Just a wee bit. So as not to scare me.

Here came a girl, a student. I was approaching her and would pass her. I looked neither to the left nor the right. I heard the sharp gasp as the girl went by.

Beautiful sidewalk, white and even.

In a few hours my classes will be over and I can go back home legitimately, I thought. I will study and I will take another shower and I will not think about Friday night. I will take a pain pill and I will sleep without dreams.

During that longest walk to class, as I caught the faces of those who passed me from the corners of my eyes, a film of that night played over and over in my head: the hand clamping over my mouth, the pillow over my face, the beating, the rape, the pain in Mimi’s face. Over and over, as my feet moved forward, I relived that night. The projector in my mind was running that movie continuously, and I had no means to switch it off. I wondered if I would always watch that movie; the audible tortured thudding of my own heart on the soundtrack, the visual shaft of moonlight, the intangible presence of death.

I must’ve seen it ten times before I reached my classroom. I glimpsed Theo Cochran during one of the in

termissions. He nodded to me silently, solemnly, from his desk beyond the open door to his office. He knew. I nodded stiffly back, the screen jumped, the movie sped on.

My tunnel vision was serving me well. But I felt the silence in the classroom as I entered; so different from the silence of admiration that had greeted me the first day. Led Zeppelin T-shirt wouldn’t whistle at me now. I sat like a stone at my desk. I heard the sound of the class bell, then the belated footsteps of Dr Haskell, half a minute late as he’d been ever since the first day. Those footfalls stopped short in the doorway. He had seen me. Then they resumed at a staccato pace to his lectern, and he entered my tunnel of sight. He was white. Every line in his face was deeper, all those grooves and seams etched into the flesh. He started to say something. He looked away.

Go on and speak, I begged him silently. Mention it. If you acknowledge it, it won’t be so bad.

But the Stan Haskell who couldn’t tolerate seeing even his lover after she’d been assaulted wasn’t going to speak. To borrow from Cully’s simile, he was going to pretend he didn’t notice the gigantic green wart on my face.

That might have made some women feel better. It scared the hell out of me. If other people pretended it hadn’t happened, I’d be left alone watching that movie in the dark.

‘In our last class . . .’ Stan Haskell began jerkily.

And there I was. Alone in the dark. A restricted audience; and no popcorn.

* * * *

Barbara Tucker was waiting for me in the hall after class. She flinched when we were face-to-face. I was getting used to that. She drew herself together and laid her hand on my arm. I felt movement on either side; my classmates were departing very slowly, passing me reluctantly, as if they wanted to stop. Stan Haskell had brushed by as soon as he could, casting one unreadable glance at us.

Gradually I became surrounded by people, as though Barbara and I had formed a dam to hold back their flow. We were all quiet for a long moment. Then the chunky blonde girl who sat to my right in class said, very formally, ‘I don’t want to intrude on your privacy, Nickie, but you have my complete sympathy, and I hope they catch whoever did it. And I hope he resists arrest and I hope they shoot him dead. For Dr Tucker, too.’ She said this in one breath, touched me gently on the shoulder, and marched off down the hall. There was a chorus of ‘Right’ and ‘Me, too,’ and then a loud and shrill ‘Kill the son of a bitch’ from my dear Led Zeppelin T-shirt.

‘Sisterhood, Nickie,’ said a tiny girl named Susannah with great earnestness. I tried to smile, which caused a cut on my lip to open and bleed. The militance that had filled the hall altered to sick horror.

‘Thank you,’ I mumbled, so the poor things could go.

Barbara’s hand on my arm began to urge me toward the women’s bathroom. She awkwardly pulled a tissue from her purse with her other hand and dabbed at my lip as we reached the door. We sat on a hideous brown couch. Barbara gave me a cigarette and lit it. Her face twisted.

‘For God’s sake,’ I said furiously, ‘don’t cry.’

‘Neither of us needs that, I know,’ she said. She gulped a few times. ‘Okay. Do you think there’s any chance they’ll catch him?’

‘Minimal, in my case. No fingerprints. No one saw anything, least of all me. Except maybe Attila the cat. It was too dark.’

‘Same here. The first thing the police asked me was, “Is he black?” ’ Barbara said grimly.

‘White. I could tell by the voice.’

‘Me, too. I think I’m so damn fair-minded. But you know, that’s the first fear I had when he grabbed me. Is it a black? The great racist bogeyman rises again.’ She brooded over that for a moment while she put out her cigarette with a vicious grinding motion. ‘What’s made this thing a nightmare for me is how Stan hasn’t been able to handle it. I haven’t seen him away from the college since it happened.’

Right now, I didn’t give a tinker’s damn about how Stan Haskell was handling it. I was worried about me handling it.

‘He can’t deal with it at all,’ Barbara continued. ‘I can’t fathom his attitude. He’s a caring man, he surely believes in the equality of women, but he can’t come to terms with me being raped at all.’

‘Cully says some men are just embarrassed,’ I offered. Then I remembered that I’d suspected he was counseling Barbara, that he must have formulated the advice he’d given me from his experiences with her.

There had been a flatness in my voice that had penetrated to Barbara. She flushed. ‘You have enough problems without me burdening you with mine,’ she said.

I realized I was doing it again. Shoving her off. ‘Barbara,’ I said, ‘we share something pretty unique. I can say this to you, I think. Screw Stan. Let him grow up on his own. He’s not tough. We are. We’re here. We’re going on. Not all men are like him. You’ve lost something that must have been pretty wonderful. But we’re here, alive.’

She sensed what I was saying, but it didn’t satisfy her, of course; I’d had no right to expect it would.

‘Anyway,’ she said finally, ‘I couldn’t go to bed with him, or anyone, now. Maybe after a long time. With care. A lot of care.’

That hadn’t been a prime concern of mine, since I hadn’t any partner. But I suddenly wondered how that was going to be for me.

We had been wandering through our separate fears for a couple of minutes when Barbara roused herself to ask me how I was physically.

‘No broken bones. The dentist tomorrow – I expect a lot of dental work. The eye doctor said Saturday that there wasn’t any permanent damage to my eyes, just bruising. I’m sore, and stiff, and I hurt like a sick dog. But I’ll get over all that. Mostly, I’m just mad. Barbara – do you hate?’

She flipped the clasp of her purse open and shut a couple of times. She pushed her glasses up on her snubby nose. At last she looked at me directly; I saw something naked behind those glasses.

‘For the first time in my life, I frighten myself,’ she said.

‘I know exactly how you feel. What can we do about it?’

‘There must be something. I’m torn up inside. Sometimes’ – and she pushed a wisp of hair behind her ear – ‘I can’t believe that I can walk and talk and teach class and tell people good morning . . . and all the time I’m carrying this terrible cancer inside me.’

‘We can pool what we know. We can think, we can figure.’

‘The police are professionals at that.’

‘It happened to us.’

‘I’ll tell you one thing I know that I don’t think the police took much stock in. He knew me. He didn’t just know my first name. He knew me.’

I took a deep breath. ‘He knew me, too.’

‘All right,’ Barbara said with a briskness she hadn’t displayed in a long time. ‘We’ll do it. Think about everyone you know. Write names down.’

‘I’ll make a list,’ I said. This was going to be a different list from any I’d compiled before. ‘We’ll compare. It’s a pity Heidi Edmonds isn’t here at Houghton anymore.’

I straightened up. I felt my shoulders brace. Even probably futile action was better than no action. In my heart I was quite sure that the trained, professional police would do the best job possible. And in New York, our plan would have seemed laughable. But here in Knolls . . .

‘I think mad is a good way to take it,’ Barbara was saying consideringly. ‘The little girl – she really was, you know – who got raped last summer; she got sad. Heidi was one of Stan’s students. He told me she became so frightened she wouldn’t even go to the bathroom without someone to go with her.’

‘Oh, I’m scared all right,’ I said grimly. ‘It takes an hour and sometimes a pill to get me to sleep. Then I keep waking up. But going away isn’t the right thing for me. It may yet get to be too much for me here, but I’m going to try to stick it out.’

‘I have to stick it out here, I have no option,’ Barbara said. ‘The job. Speaking of the job, I have to go meet a class.’ She gathered together the parap

hernalia teachers and students carry with them everywhere. ‘If you ever need me, call me. Anytime.’

We clasped hands briefly and tightly. When I left for my next class, I felt better. I was not alone in that darkened room anymore.

And I made it somehow through the rest of the school day.

* * * *

When I got home, a locksmith was putting new hardware on all the windows and doors. Mimi was following him from room to room, a cigarette lit but disregarded in her hand. I was appalled by my mental estimation of the cost of this. I cornered Mimi to tell her I’d pay for it. With one terse phrase she turned me down. When the locksmith left a check tucked in his pocket and a smile on his face, Mimi asked me if I was ready to move upstairs with her. I’d been sharing her king-size bed for the past two nights; she had been as restless as I.

‘No,’ I said. ‘I’ll keep my bedroom. And sleep in it, starting tonight.’

‘That’s crazy,’ Mimi said bluntly. ‘There are two rooms upstairs you could have. All it’ll take is a little time and muscle.’

It was foolish of me to insist I would sleep in my own bedroom. Sheer bravado, rather than courage. Having determined I wouldn’t let this get me down, I was bullheaded enough to persist in any resolution, however ill-reasoned. I should’ve made some concessions to myself, given myself a little leeway. I should have known my life would never again be exactly as it had been.

‘With all those locks you put in,’ I insisted, ‘no one in the world could break in unless he was a professional and had lots of undisturbed time.’

‘Then, Miss Martyr,’ she said tartly, ‘Cully’s going to sleep in the dining room right opposite your bedroom.’

‘There’s no need for . . .’

‘Just cut out this heroine stuff,’ Mimi said. Her voice soared high and thin. I saw her hands shake when she lit another cigarette. ‘You may be willing to be an iron woman, but my God, I’m scared.’ Even the cats, sleeping together peacefully for once, lifted their heads at the warning note in her voice. I felt very small: as my father used to say, ‘knee-high to a grasshopper.’

Dead Ever After

Dead Ever After Grave Sight

Grave Sight Dead Until Dark

Dead Until Dark Real Murders

Real Murders Wolfsbane and Mistletoe

Wolfsbane and Mistletoe All the Little Liars

All the Little Liars Dead to the World

Dead to the World Club Dead

Club Dead Dead in the Family

Dead in the Family The Sookie Stackhouse Companion

The Sookie Stackhouse Companion All Together Dead

All Together Dead Dead as a Doornail

Dead as a Doornail Sleep Like a Baby

Sleep Like a Baby Night Shift

Night Shift A Touch of Dead

A Touch of Dead Living Dead in Dallas

Living Dead in Dallas Dead Reckoning

Dead Reckoning Deadlocked

Deadlocked Dead and Gone

Dead and Gone From Dead to Worse

From Dead to Worse Definitely Dead

Definitely Dead Last Scene Alive

Last Scene Alive Grave Secret

Grave Secret Three Bedrooms, One Corpse

Three Bedrooms, One Corpse The Russian Cage

The Russian Cage Shakespeares Counselor

Shakespeares Counselor Dead of Night

Dead of Night Shakespeares Trollop

Shakespeares Trollop One Word Answer

One Word Answer Shakespeares Champion

Shakespeares Champion Shakespeares Christmas

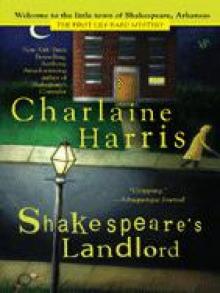

Shakespeares Christmas Shakespeares Landlord

Shakespeares Landlord Poppy Done to Death

Poppy Done to Death Dead Over Heels

Dead Over Heels An Ice Cold Grave

An Ice Cold Grave The Julius House

The Julius House Day Shift

Day Shift A Fool And His Honey

A Fool And His Honey A Longer Fall (Gunnie Rose)

A Longer Fall (Gunnie Rose) The Complete Sookie Stackhouse Stories (Sookie Stackhouse/True Blood)

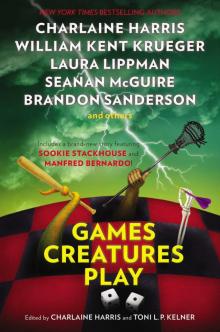

The Complete Sookie Stackhouse Stories (Sookie Stackhouse/True Blood) Games Creatures Play

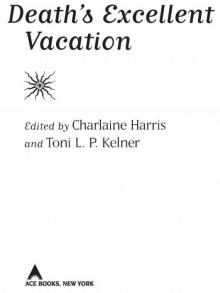

Games Creatures Play Death's Excellent Vacation

Death's Excellent Vacation (LB2) Shakespeare's Landlord

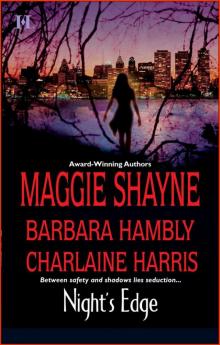

(LB2) Shakespeare's Landlord Dancers In The Dark - Night's Edge

Dancers In The Dark - Night's Edge Last Scene Alive at-7

Last Scene Alive at-7 Deadlocked: A Sookie Stackhouse Novel

Deadlocked: A Sookie Stackhouse Novel Dead But Not Forgotten

Dead But Not Forgotten (4/10) The Julius House

(4/10) The Julius House Dead Reckoning: A Sookie Stackhouse Novel

Dead Reckoning: A Sookie Stackhouse Novel A Touch of Dead (sookie stackhouse (southern vampire))

A Touch of Dead (sookie stackhouse (southern vampire)) (3T)Three Bedrooms, One Corpse

(3T)Three Bedrooms, One Corpse An Easy Death

An Easy Death A Secret Rage

A Secret Rage Many Bloody Returns

Many Bloody Returns![Harper Connelly [3] An Ice Cold Grave Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/25/harper_connelly_3_an_ice_cold_grave_preview.jpg) Harper Connelly [3] An Ice Cold Grave

Harper Connelly [3] An Ice Cold Grave Dancers in the Dark and Layla Steps Up

Dancers in the Dark and Layla Steps Up Small Kingdoms and Other Stories

Small Kingdoms and Other Stories Dead Ever After: A Sookie Stackhouse Novel

Dead Ever After: A Sookie Stackhouse Novel Dead in the Family ss-10

Dead in the Family ss-10 Sweet and Deadly aka Dead Dog

Sweet and Deadly aka Dead Dog An Easy Death (Gunnie Rose #1)

An Easy Death (Gunnie Rose #1) The Complete Sookie Stackhouse Stories

The Complete Sookie Stackhouse Stories Sookie Stackhouse 8-copy Boxed Set

Sookie Stackhouse 8-copy Boxed Set Sweet and Deadly

Sweet and Deadly Crimes by Moonlight

Crimes by Moonlight Dead Ever After: A True Blood Novel

Dead Ever After: A True Blood Novel Dead Ever After ss-13

Dead Ever After ss-13 After Dead

After Dead Dancers in the Dark

Dancers in the Dark (LB1) Shakespeare's Champion

(LB1) Shakespeare's Champion A Bone to Pick (Teagarden Mysteries,2)

A Bone to Pick (Teagarden Mysteries,2)